Letters from Kuujjuaq: A Northern Journey Continued

- Michelle Kwok

- Apr 8, 2025

- 10 min read

It had been almost a year since I last set foot in the North, but in many ways, I never truly left. Through virtual clinics and e-consults, I’d stayed connected with communities, intentionally involving residents to give them a sense of what healthcare looks like in remote northern settings. Back home in Montreal, I’d bump into Inuit patients at the hospital, recognizable by their nasatuinnak hats. I’d ask which community they were from and what had changed. Somehow, the North would always find its way into the South.

There was a sense of anticipation this time, anxiety mixed with excitement. In the past year I’d had the chance to share updates on our northern work at CSACI in Banff, AAIQ in Tremblant, McGill High Value Care Symposium, at the McGill Global Health Night, and with Canadian delegates attending the Lausanne Congress. In February, I co-presented a seminar at the AAAAI/WAO Joint Congress in San Diego with Dr. Ghislaine Isabwe. We discussed our outreach projects in Nunavik and Rwanda and what it means to deliver allergy care in underserved areas.

Now, the time had come to return.

Over the past month, I’d been in touch with the team at the Nunavik Research Centre about a new environmental health project. And as always, there had been plenty of coordination with the nursing liaison team in Kuujjuaq — the real backbone that keeps the clinics running.

This time, I was traveling with Dr. Mariam Eldaba, a former nephrologist from Egypt and now a PGY-4 allergy fellow at McGill. We first met at the 2022 CAAIF Gala in Québec City, and not long after she moved to Montreal, she mentioned her interest in Indigenous health during an impromptu visit to the Kahnawà:ke Pow Wow.

After clinic, Mariam and I stopped by the bulk store to stock up on herbs, spices, dried fruits, and nuts for food challenges and skin testing. And of course, the most important discussion: what food to pack? We settled on some comforting choices: pasta, rice, salmon, baba ghanoush, pita, salad, and of course, vegetable dumplings. A quick trip to the dollar store for mini bags, labels, and a mortar and pestle, and I headed home to finish packing and labeling.

Wednesday, March 26, 2025

Early that morning, Mariam and I made our way to the Montreal airport. We checked in with Canadian North and headed to our gate. As the plane landed in Kuujjuaq, I could already feel the weight of southern life fall away and be replaced by the beauty of the open land. It was -15°C, not bad for late March, and everything felt quiet and still.

We were met at the airport by Guy Bergeron, Chef du service de liaison et télésanté, who has been working in Kuujjuaq for 17 years. Always enthusiastic about sharing the beauty of the North, Guy has helped coordinate many visiting clinicians over the years. My luggage, however, was not there. The plane continued to Iqaluit, and I wondered if my bag had gone with it.

We got into the vehicle and started our drive through town. Here, nobody wears seatbelts, mostly out of practicality. In fact, if you do wear a seatbelt, you would immediately be called out as an over-cautious southerner. License plates are technically not required either, since the roads aren’t connected to any highway. Guy mentioned a certain “look” that immediately gives away a first-time visitor. Everything would seem fascinating: the colourful buildings, the snowmobiles, the King Air plane taking passengers to smaller communities, the icy roads, the crisp air. But for locals, arriving in the North is like taking the bus to work – everyday, essential, and unremarkable.

We stopped at the local store to grab a few essentials. Surprisingly, some of the prices were quite reasonable and comparable to the South, thanks to the Nutrition North program that subsidizes certain food items in remote communities. After dropping off our items at the transit house, we headed to the hospital. There, we were warmly welcomed by pivot nurse Nathalie Harbour, Simon Trépanier, and Louisa Annanack, the clinic coordinator who keeps everything running smoothly, and Sandrine Dobson, who helped organize logistics for visiting staff. Nancy Veilleux, the nurse who had coordinated the teleclinics and prepared the patient list for this trip, wasn’t there that day, but had helped with organizing all the patients. It was a quiet start otherwise, with only one patient that afternoon, so we spent the rest of the day reviewing charts for the next day.

We wheeled our boxes upstairs into the archives, then made our way to the wards to find someone who could help with the luggage situation. I approached a nurse I’d never met before and asked if there was any way to borrow scrubs. Without missing a beat, she said, “I got you.” She handed me toiletries, took me to the laundry room, and helped me find extra scrubs. She even offered additional meal tickets in case we needed them. That kind of kindness and camaraderie is something I’ve come to associate with working in the North.

Back at the transit house, we met a medical student from Université Laval who had just finished her outreach in Quaqtaq and was stuck on her return due to a blizzard. She shared her hopes of becoming a rural family doctor, and it was encouraging to see another trainee engaging with northern and remote practice so early in her journey. We then enjoyed salmon, pasta and salad, to end the day.

Thursday, March 27, 2025

The next morning, we started clinic with drug challenges for patients from Kuujjuaq who had been referred for suspected antibiotic allergies. We saw several children labelled as allergic to amoxicillin, often from hives that appeared during treatment for otite moyenne aiguë, which is quite common here. But hives can be misleading. They are often caused by the infection itself, not the antibiotic. Ruling out a true allergy not only expands local treatment options but can also save families from having to travel down south for care that could be managed closer to home.

In the afternoon, we shifted to food allergies. Avoiding common foods, or living with the fear of a possible reaction, can affect quality of life, especially in a region where food choices are already limited. Being able to safely confirm or rule out a food allergy often brings peace of mind and some clarity.

Most of the afternoon patients had been flown in from Tasiujaq and Kangiqsujuaq (Wakeham Bay). The Kangiqsujuaq group arrived ahead of schedule, and suddenly we had a full clinic. The liaison team worked behind the scenes to handle all the logistics such as flights, lodging, and follow-up.

Partway through, a family doctor asked when we’d be coming back, mentioning they’d love to take us out on the land next time, maybe on a four-wheeler. One of the hospital staff asked too, and some of the patients. Continuity matters in a place where care is built on connection. It shows people you’re not just passing through.

After finishing up the paperwork, we caught a glimpse of a brilliant pink and purple sunset before heading back to the transit house for dinner. There, we were joined by a Université Laval family medicine resident in his last week of rotation in Kuujjuaq.

Friday March 28, 2025

I started the morning with a walk in the snowy –20°C weather, past St. Stephen’s Anglican Church, over the bridge, past the school, CIBC, and CBC North, before turning back.

At the hospital, I spoke with one of the family physicians about antibiotic allergies. We discussed the possibility of their team managing low-risk drug challenges locally, while leaving the higher-risk ones to us. It could shorten wait times and build local capacity so that more care can be offered using the resources already on site.

Then, the day began with more food allergy testing, mostly for patients flown in from Quaqtaq and Kangiqsualujjuaq (George River). The kitchen staff quickly came to know us well, as we kept requesting all kinds of ingredients to test, such as apples, raisins, even chocolate cake. They were always generous. I had noticed them the day before, cutting parsnips and rutabagas by hand to prepare homemade meals. Back in residency, I had mostly learned to avoid hospital cafeteria food, but I was starting to see why this one was so popular. The food was actually good. Yesterday’s menu was a salmon burger. Today: mac and cheese, chicken schnitzel with coleslaw, veggie soup, and two kinds of dessert.

At one point, the mother of one of our patients returned with a frozen char. She told us she had wanted to bring fresh char and said the best ones come from Kangirsuk, but the plane hadn’t landed. Later, we heard there had been a blizzard, grounding the flights. Guy had been going to the airport voluntarily after lunch each day to check on my luggage, but still nothing. Even with Canadian North in both Toronto and Montreal involved, the bag couldn’t be found. But strangely, I never really felt like I was missing anything.

There were two reunions that stood out for me. The first was meeting the daughter of an interpreter I had worked with at the CLSC in Quaqtaq two years ago. She shared that she hopes to become a therapist in the North because she grew up here, understands the realities her community faces, and wants to support others in ways that are culturally safe and grounded in local knowledge. I told her about reconnecting with her mom in Montreal last year, and how she looks just like her mother.

The second was with a family I first met during my initial trip north in 2023. Their daughter, now growing into a confident young woman, brought her friend—also a patient—and we caught up briefly. It was heartening to reconnect, to see how people had grown, and to be reminded once again of the beauty of the region through her mother’s words.

After clinic, we stopped by briefly to visit Tivi, the local art store that sells hand-beaded earrings, sealskin gloves, sculptures, and other crafts made by artists from the region. Back in the transit, we shared dinner, and we played board games our new housemates who felt more like old friends by the end of the night.

Saturday, March 29, 2025

On our last morning in Kuujjuaq, we visited the Nunavik Research Centre, where we were welcomed by Dr. Michael Kwan, a long-time resident of the region originally from Hong Kong. After completing his PhD in Environmental Toxicology at King’s College London, Dr. Kwan spent over a decade working in the U.K. before moving north in 1996 to join the Makivik Corporation. Now retired, he continues to live in Kuujjuaq and remains closely connected to the Centre’s work.

While waiting for Dr. Noah Brosseau, the assistant director of the Centre, we were given a short drive through town before beginning a full tour of the lab. The Centre conducts wide-ranging environmental research, especially focused on contaminants in fish and marine mammals, much of it driven by direct requests from local communities. If a village expresses concern about nearby mining activity, diesel spills, or food safety, the Centre sends a team to collect sediment, water, and tissue samples, often by helicopter to extremely remote sites such as Upper George River.

“It’s not just research for science’s sake,” Dr. Kwan said. “The project must be useful for the community. No matter how brilliant the science is, if it doesn’t benefit people here, it’s not a priority.”

As we walked through the lab, Michael shared stories about some of his longtime colleague Peter May, a respected figure in the region’s environmental work. Peter comes from the well-known May family of Kuujjuaq: his brother, Johnny May, was the first Inuk bush pilot in eastern Canada, renowned for flying medevacs and launching his Christmas Day candy drop from a small plane over Kuujjuaq each year. Their sister, Mary Simon, is now the first Inuk Governor General of Canada.

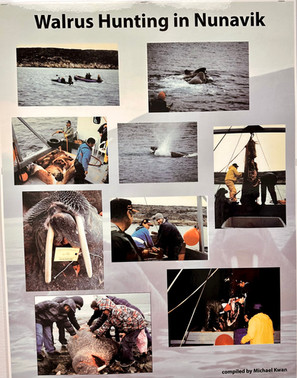

One of the most memorable programs we learned about was the Trichinella testing system for walrus meat. Walrus is a vital part of the diet in many coastal communities, especially during summer and fall hunting seasons. The hunt is communal, and the meat is shared widely. However walrus can carry Trichinella, a parasite that causes serious illness if not properly cooked. To prevent outbreaks, the Centre runs a free, voluntary testing program. Hunters send in the tongue, where the parasite is most likely to be found, and results are delivered within 24 hours. If no parasites are detected, the meat is deemed safe. Results go to the physician on duty, who informs the mayor, who shares the update over FM radio. During peak season, the lab often stays open late to ensure communities receive answers in time. It is an example of a simple, trusted system that works in step with local rhythms.

What stood out most to me was how deeply embedded the Centre is in community life. Over the years, many high school students have started helping in the lab, gaining hands-on experience and often returning in more senior roles. One of them is now leading the whole department. Barrie Ford, now Director of Makivik’s Department of Environment, Wildlife, and Research (DEWR), was born and raised in Kuujjuaq and studied Wildlife Biology at McGill University. He began his career at the Research Centre, later served as deputy director, and is now the first Inuk to lead DEWR.

After the tour, we made our way to Michael’s home, which he had designed and built with a local contractor. It sits quietly on a hill overlooking the open land. Inside, the wooden interiors were warm, with bamboo blinds letting in the filtered light. The shelves were lined with historical artifacts, old maps of the North, and cultural pieces from around the world, and a hand-carved wooden model of Nunavik by a local woodworker.

Michael served us green tea in porcelain cups, and we sat for a while watching the birds flutter outside the window. He told us about the traditional methods he still uses when cooking and how he’s managed to ship up a full stock of Chinese ingredients from the South. At one point, he started talking about mapo tofu, its Sichuan origins, the correct way to cook it, and I realized I had been eating it wrong my entire life. It made me smile. After all, who would have thought I’d be talking about tofu with another Chinese person in the middle of the Arctic?

Reluctantly, we made our way back to the transit house to gather our things, then headed to the hospital one last time to say goodbye. The nursing staff were already busy preparing for the week ahead. We exchanged warm farewells, spoke of staying in touch, and made plans to discuss the next virtual clinics, and another future collaboration.

Guy drove us to the airport, as he has done for countless visitors over the years. We thanked him, said goodbye, and boarded the plane. And once more, we crossed that invisible line dividing North and South, back into the world we had left behind.

I really enjoyed reading about your visit to Kuujjuaq. I spoke to my son Noah this weekend and he told me about your research project on pollen. He was collecting specimens that morning. It’s great to see research initiatives being carried out in the Northern regions.

Interesting story! I love how you enjoy every step of your visit while exploring new things. That makes the trip fun and memorable. Well-done and can't you wait to be back there soon!