Systems and Belonging

- Michelle Kwok

- 3 hours ago

- 9 min read

Monday, February 09, 2026

Oxford, England

I had arrived in Oxford the day before, coming from London, which had felt fast paced and large. As the bus pulled into the city, I felt a sense of grounding. Oxford was a return to a place I knew.

This was my third time in Oxford, and the city no longer felt as foreign or imposing. While it remains large, there was a growing sense of comfort moving through it. The business school, and our cohort within it, has started to feel like its own college. Seeing familiar faces again made it easier to settle into the week.

The clubhouse at Saïd was open with its usual excellent coffee and snacks. There was a green cake labelled “moss cake,” which we took turns trying to identify. I took the first bite and could only decipher that it tasted plant-like, almost healthy. It turned out to be a spinach cake with cream cheese frosting, which reminded me of a blog that hides vegetables in desserts. Not everyone was convinced.

We began our afternoon with an optional pre-module enrichment session which normally falls on the Monday. I brought my moccasins from an Indigenous-founded brand in Canada. They kept my feet warm in the cold lecture hall.

In the early evening, we had an student-led session organised by Matthias from Switzerland, with Michael McCord of Milliman discussing microinsurance. He had flown up from Malawi just for the talk and spent two days in Oxford before flying onward to Uganda. The session came alive from his years of lived experience in different countries, and ran well past the scheduled end time. Afterwards, a small group of us went out for dinner to continue the conversation.

Tuesday, February 10, 2026

We started the day with two surprises. Beside each nameplate were hand-beaded Kenyan bracelets, personalised with our names and national flags. In the weeks leading up to the module, our cohort WhatsApp group had been active with jokes by Ben from Kenya about bringing lions through customs. We had been kept in suspense about what these “lions” might be, and that morning we found out. Ben shared that his wife, who runs a beadwork business, had designed the bracelets.

Sami from Pakistan also brought cashmere scarves for the women in blue and camel, reflecting the colours of Saïd. These gestures were generous and thoughtful.

We then launched into our first full academic day of Module 3, which was when much of the preparation began to come alive for me. In the three weeks beforehand, we had completed extensive readings and participated in group discussions online. As a cohort, we were asked to identify problems from our own contexts, discuss them together, and prioritise which ones to take forward. From this process, several issues were selected, and we were divided into groups to continue working on throughout the week.

I found this work particularly meaningful. Our group focused on improving access to quality healthcare in rural and underserved areas in Pakistan. As we discussed the issue with colleagues from Jordan, the rural United States, and Austria, it became clear how many of the underlying challenges were shared across settings. Problems that had initially felt specific to one context echoed strongly in others. The exercise highlighted how global many of these issues are, often differing more in degree than in kind.

At lunch, the cheese plate stood out, with Oxford Blue, Somerset Brie, Red Leicester, and aged Cheddar, served with figs and grapes. Oxford Blue brought back a memory from the end of Module 1, when a few of us shared some together at the Covered Market before heading back to London.

One of the afternoon exercises began with each of us individually diagramming how to cook rice. What felt straightforward quickly revealed how many assumptions were embedded in a familiar task. In my own diagram, I measured the water using my finger, while the person next to me focused on precise ratios.

We then repeated the exercise as a group, bringing our diagrams together into a single version. As we tried to agree on a shared process, questions about boundaries, sequencing, and hidden factors surfaced naturally. The exercise made visible how even simple processes require negotiated assumptions when people work together.

Photo credit: Dr Gugulethu Moyo

Afterwards, we attended a networking event with the Global Health Society. It was nice to reconnect with Dr Faojia Sultana, the president, and to meet Sachi Chan, the events coordinator. Discovering that she was also Canadian felt like an easy point of connection in an otherwise international setting.

Wednesday, February 11, 2026

Wednesday unfolded around the idea that how we see something determines what we can change. We began with the Zipline case in Rwanda, where drone delivery improved access to blood in remote clinics. It was an impressive logistical innovation, yet it carried a deeper lesson. A system does not transform simply because one part becomes more efficient. An intervention must sit within relationships, incentives, and trust if it is to endure.

That theme carried into our discussion on leadership mindset. We were asked to name the qualities we respect in leaders. The answers centred on postures rather than prestige. Leaders who listen carefully. Leaders who act with integrity. Leaders who delegate with trust. They are habits that can be cultivated.

We debated whether leaders are born or made. For me, the answer felt clear. While temperament may differ, the traits we described are formed over time. Leadership is largely shaped if one chooses to grow into it. That conviction is part of why I am in this programme.

Psychological safety surfaced as something even more fundamental. Systems cannot evolve if people are afraid to speak honestly. Teams cannot learn if uncertainty is concealed. Safety is not simply a desirable trait in a leader. It is the condition that allows systems change to take root.

In the afternoon, our small groups continued refining our projects. What appeared straightforward at first proved difficult. Formulating a problem statement required sustained debate. Ideas were broad and had to be defined and redefined, bounded and clarified. In our group, we chose to focus on the patient journey. Tracing one person’s path through the system revealed friction points that statistics alone might overlook. The work felt slower than I expected. I realised how often I have wanted to act before fully understanding where leverage lies.

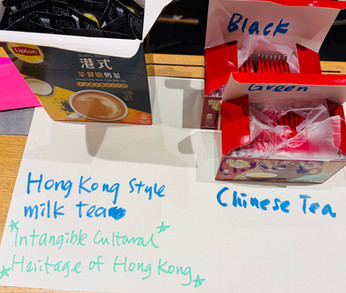

After class, had our Lunar New Year gathering, hosted by Bell from Hong Kong, Mike from Singapore, myself. Many of our colleagues arrived wearing red. One had gone out of his way to find something red in between lectures for the occasion. Our course coordinator wore a Chinese-style top. Red shoes, scarves, and shirts appeared around the room.

After a long day of discussion, they listened with genuine interest as we shared the history and regional traditions of Lunar New Year. We spoke from our lived histories. I sang 燕子 ("The Swallow"), 曲曼地 ("Qu Man Di"), 茉莉花 ("Jasmine Flower"), and 那就是我 ("That is Me"), sharing the stories behind each song. Bell brought 笑口棗 (smiling sesame balls), 角仔 (crispy fried dough twists), and 利是糖 (New Year sweets) from Hong Kong, along with 利是封 (red pocket envelopes) for the occasion. Mike brought 鳳梨撻 (pineapple tarts), 鹹蛋魚皮 (salted egg fish skin), and 威化餅 (wafer biscuits) from Singapore. We practised calligraphy, writing 福 and 吉 for fortune and auspiciousness, and watched the ink settle into red paper.

Later, we went out for hot pot to celebrate the Lunar New Year and to warm ourselves against the winter cold. We guided our colleagues in choosing ingredients, a soup base and sauces for dipping. Some gravitated toward the spicy broth with confidence, while others cautiously tested their tolerance. It was good to sit together outside the classroom and to celebrate communally.

Thursday, February 12, 2026

Photo credit: Dr Gugulethu Moyo

We began the morning with the marshmallow challenge. In small groups, we were given spaghetti, tape, string, and a marshmallow and asked to build the structure that could hold the marshmallow at the greatest height. We tried very hard to build the tallest possible structure within the time limit, but it collapsed.

We were told that MBA students often perform worse than kindergarteners on this task. Children tend to test early. They place the marshmallow on top from the beginning and adjust as they go. Many adults spend most of the time planning, only to discover too late that the structure cannot bear the weight.

In the debrief, I realised how familiar it felt. As a physician who also works in research and system improvement, much of my training has rewarded careful planning and risk calculation. Yet in my outreach work in the North, I rarely have the luxury of full information. Weather shifts, plans change, and patients present in ways that do not follow the textbook. Improvisation and creativity are not optional.

We revisited the idea of the hero narrative in leadership and the need to move from an egocentric model toward a more eccocentric one. The conversation named ecological, social, and spiritual divides underlying visible crises, including a loss of shared meaning. I had seen this way of thinking in other contexts where land, community, and meaning are understood as interconnected, but had not heard it framed within leadership theory.

The distinction between reducing harm and regenerating systems was particularly clear. Reducing harm stabilises what is already strained. Regeneration asks how a system might actively restore and strengthen what has been eroded. It echoed earlier conversations I had about redemptive entrepreneurship so much that I messaged the mentor who first introduced that framework to me.

The rest of the morning and early afternoon were devoted to preparing our fifteen-minute presentation on the Pakistan case. Other teams were equally focused, using breaks to continue refining their work.

In the afternoon, we moved into the Fishbanks simulation, a common resource exercise in which each team attempted to maximise returns from a shared fish stock. Early rounds encouraged expansion. By the time depletion was obvious, recovery was already difficult. The debrief centred on collective governance and the commons. Sustainable outcomes depend on coordination, transparency, and rules shaped by those who rely on the shared resource.

Leadership also appeared in quieter forms. When I misread a timing detail, the course coordinator sent a message to check where I was. When our brainstorming materials left behind the day before were cleared away, one of the teaching fellows tried to locate them and apologised when they could not be found. These small actions reflected attentiveness within the system itself.

In the evening, I attended choral evensong at Merton College, a service held regularly and open to anyone who wishes to attend. The chapel was lit by candlelight, and the acoustics carried the choir’s voices with remarkable clarity. Scripture was read, prayers were spoken, and we joined in the responses. The stillness of the space contrasted with the intensity of the day. It felt sacred.

Later, we gathered at Corpus Christi for our formal dinner, a tradition we observe once each module. This time we chose black tie. The room was more modern and brightly lit than some of the older halls. As usual, we sat alongside faculty, and conversation carried easily across the table. I was asked to say grace in Latin and read the passage carefully, aware of its tradition even if I did not understand every word. The meal followed, and I had grilled oyster mushroom and aubergine with savoy cabbage, dauphinoise, and a light sauce.

Some returned home afterwards, while others continued the evening out.

Friday, February 13, 2026

Comments